In an era where institutional power often seems overwhelming and citizen voices can feel lost in bureaucratic mazes, a unique figure stands as guardian of fairness and accountability: the Ombudsman.

Known in Swedish as “Ombudsmänner” (plural form), these independent officials serve as essential bridges between ordinary citizens and the complex institutions that govern modern life.

Far more than mere complaint handlers, Ombudsmänner represent a profound democratic innovation—one that transforms the abstract ideals of justice and transparency into tangible, everyday realities for millions worldwide.

The concept might seem simple at first glance: an independent official who investigates complaints against government agencies, corporations, or other institutions.

Yet this simplicity masks a sophisticated mechanism for democratic accountability that has evolved over centuries and now spans continents, adapting to serve societies from Scandinavia to South Africa, from university campuses to multinational corporations.

The Swedish Innovation That Conquered the World

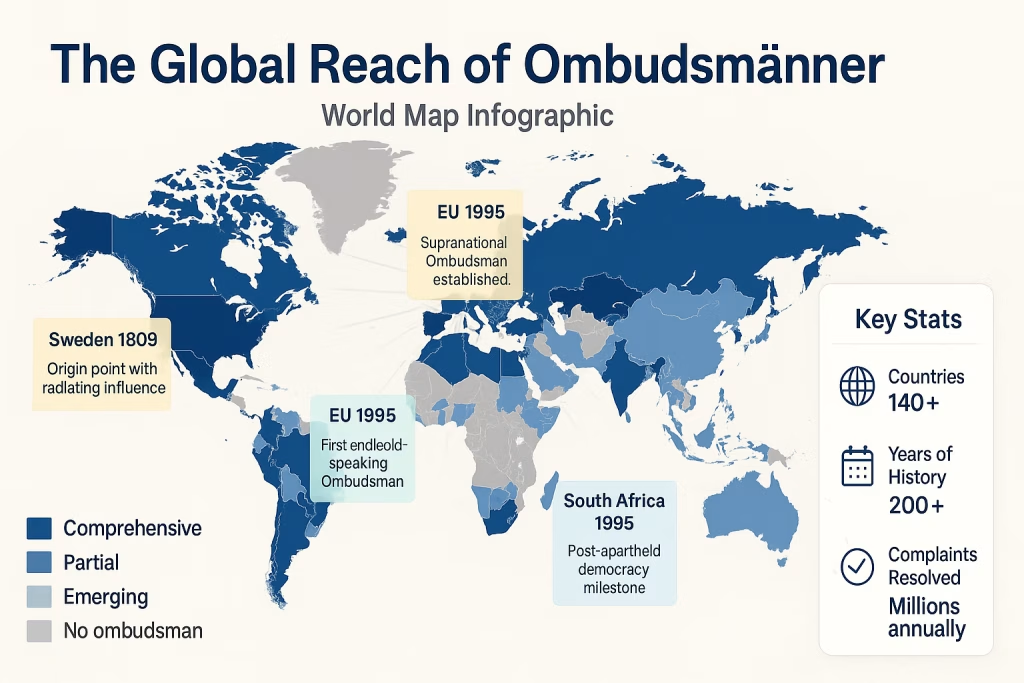

The story of the Ombudsman begins in 1809 in Sweden, born from the ashes of military defeat and political upheaval. Following a disastrous war with Russia, Sweden underwent a constitutional revolution that sought to prevent future abuses of power.

The Swedish Parliament established the office of Justitieombudsman—literally “justice representative”—as an independent authority to ensure that government officials followed the law and treated citizens fairly.

This Swedish innovation emerged from a simple yet revolutionary premise: citizens needed a champion who could investigate grievances against the powerful without fear of retribution.

The early Swedish Ombudsman possessed remarkable independence, appointed by Parliament but answerable to no political party, with the authority to inspect government offices, review documents, and prosecute officials who violated the law.

What began as a Nordic experiment gradually captured global imagination. Finland adopted the institution in 1919, followed by Denmark in 1955.

The true explosion came in the 1960s and beyond, as nations worldwide recognized the Ombudsman’s potential to strengthen democracy and enhance governance.

New Zealand became the first English-speaking country to establish an Ombudsman in 1962, triggering adoption across the Commonwealth.

Today, over 140 countries have embraced some form of the Ombudsman institution, each adapting it to local needs while preserving its core principles of independence and accessibility.

Guardians of Fairness: Roles and Responsibilities

Modern Ombudsmänner operate as multifaceted defenders of citizen rights, their responsibilities extending far beyond simple complaint resolution.

At the heart of their mission lies the investigation of maladministration—those instances where institutions fail to follow proper procedures, abuse their authority, or simply treat people unfairly.

Yet their work encompasses much more.

These officials serve as institutional mirrors, reflecting back to organizations how their actions affect real people.

When a disability pension is wrongly denied, when a student faces discriminatory treatment, when a prisoner’s rights are violated—the Ombudsman steps in not just to resolve individual cases but to identify systemic problems that require broader reform.

Crucially, Ombudsmänner operate through persuasion rather than coercion. Unlike courts, they typically cannot issue binding orders, yet their recommendations carry tremendous moral authority.

Their power derives from transparency—the ability to publicize findings and shame institutions into compliance—and from their reputation for impartiality.

This soft power approach often proves more effective than legal mandates, fostering cooperation rather than resistance from the institutions under scrutiny.

The accessibility of Ombudsmänner represents another defining characteristic. Citizens can usually file complaints free of charge, without lawyers, often through simple online forms or even verbal complaints.

This low barrier to entry ensures that society’s most vulnerable members—those who cannot afford legal representation or navigate complex bureaucracies—still have recourse to justice.

From Parliament to Prison: Ombudsmänner in Action

The versatility of the Ombudsman model becomes evident through examining its diverse applications worldwide.

In South Africa, the Public Protector—the nation’s Ombudsman—gained international attention through high-profile investigations into government corruption, including cases involving former President Jacob Zuma.

Thuli Madonsela, who served as Public Protector from 2009 to 2016, became a household name by fearlessly investigating powerful political figures, demonstrating how Ombudsmänner can serve as crucial anti-corruption forces in emerging democracies.

In the corporate sphere, financial ombudsmen have revolutionized consumer protection.

The UK’s Financial Ombudsman Service handles over two million consumer inquiries annually, resolving disputes between individuals and financial institutions without costly litigation.

Their decisions have forced banks to repay billions in mis-sold payment protection insurance, illustrating how Ombudsmänner can level the playing field between ordinary consumers and powerful corporations.

Educational institutions increasingly employ Ombudsmänner to address student grievances and promote fair treatment.

At the University of California system, campus ombudsmen handle thousands of cases yearly, from grade disputes to harassment complaints, providing neutral ground for resolution while identifying patterns that require policy changes.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, these educational Ombudsmänner proved invaluable in addressing unprecedented challenges around remote learning, grading policies, and student welfare.

The European Ombudsman, established in 1995, demonstrates the institution’s potential at supranational levels.

By investigating complaints about EU institutions, this office has exposed issues ranging from lack of transparency in trade negotiations to revolving door practices between EU institutions and private lobbying firms.

Their work proves that even in complex, multi-layered governance structures, Ombudsmänner can promote accountability and citizen engagement.

Navigating Modern Challenges

Despite their successes, contemporary Ombudsmänner face formidable challenges that test their relevance and effectiveness.

The digital transformation of government services creates new forms of exclusion and algorithmic bias that traditional investigative methods struggle to address.

When an artificial intelligence system denies someone benefits or a automated system flags them as a fraud risk, determining accountability becomes exponentially more complex.

Political pressure represents another persistent challenge. In many countries, governments have attempted to weaken Ombudsman offices by cutting budgets, limiting jurisdiction, or appointing political allies to these supposedly independent positions.

The Venezuelan Ombudsman’s office, once a beacon of human rights protection, became compromised through political capture, serving government interests rather than citizen rights—a cautionary tale about the fragility of these institutions.

Resource constraints plague many Ombudsman offices, particularly in developing nations where the need is often greatest.

Overwhelming caseloads can lead to lengthy delays, undermining the very accessibility that makes Ombudsmänner valuable.

Some offices receive tens of thousands of complaints annually but operate with skeletal staff, forcing difficult decisions about which cases to prioritize.

Yet innovative Ombudsmänner have developed creative solutions to these challenges. Many have embraced technology, using artificial intelligence to identify patterns in complaints and prioritize systemic issues.

Mobile complaint systems reach rural populations previously excluded from their services. Collaborative networks allow Ombudsmänner to share best practices and coordinate responses to cross-border issues.

The Democratic Bridge

The true significance of Ombudsmänner extends beyond individual complaint resolution to their role in strengthening democratic culture.

They serve as vital connective tissue between citizens and institutions, translating individual grievances into systemic improvements.

When patterns emerge from complaints—elderly citizens struggling with digital government services, minorities facing discriminatory treatment, businesses battling bureaucratic delays—Ombudsmänner transform these individual frustrations into actionable policy recommendations.

This bridge-building function proves especially crucial in societies with low trust in government institutions.

By providing a neutral forum for grievances, Ombudsmänner can prevent the escalation of conflicts that might otherwise destabilize social cohesion.

Their annual reports become democratic documents, chronicling not just institutional failures but also improvements, building public confidence that the system can self-correct.

Moreover, Ombudsmänner educate both citizens and institutions. They help citizens understand their rights and navigate complex systems, while teaching institutions about the human impact of their decisions.

This educational role creates a virtuous cycle: more informed citizens make better complaints, leading to more effective investigations and more responsive institutions.

Tomorrow’s Guardians: Evolution and Adaptation

As society evolves, so too must the institution of the Ombudsman. The digital transformation presents both challenges and opportunities. Future Ombudsmänner will need expertise in algorithmic accountability, data protection, and digital rights.

They must develop new investigative techniques to audit automated decision-making systems and ensure that efficiency gains from digitalization don’t sacrifice fairness and human dignity.

Globalization demands new forms of cooperation among Ombudsmänner. Cross-border issues—from multinational corporate malfeasance to refugee rights—require coordinated responses that transcend traditional jurisdictional boundaries.

Regional networks of Ombudsmänner are emerging, sharing information and developing common standards while respecting local contexts.

Climate change and environmental degradation have spawned proposals for specialized Environmental Ombudsmänner who could investigate complaints about pollution, advocate for future generations’ rights, and ensure that environmental regulations are properly enforced.

Some countries have already moved in this direction, recognizing that traditional oversight mechanisms struggle with the long-term, diffuse nature of environmental harm.

The post-pandemic world has heightened expectations for responsive, accessible governance. Citizens increasingly expect real-time responses to complaints and transparent tracking of their cases.

Smart Ombudsman offices are developing online portals that allow complainants to monitor investigation progress, access relevant documents, and communicate with investigators—bringing centuries-old institution into the digital age.

Conclusion: The Enduring Promise

The institution of the Ombudsman—the Ombudsmänner—represents one of democracy’s most elegant solutions to the eternal problem of power and accountability.

From its Swedish origins to its global proliferation, from government offices to university campuses, this institution has proven remarkably adaptable while maintaining its core mission: ensuring that power serves people, not the reverse.

As we navigate an era of rapid technological change, growing inequality, and evolving citizen expectations, the need for effective Ombudsmänner has never been greater.

These champions of justice and transparency remind us that democracy is not just about elections and legislation but about the daily experience of fairness, dignity, and respect in citizens’ interactions with institutions.

The future success of Ombudsmänner will depend on their ability to evolve while preserving their essential characteristics: independence, accessibility, and moral authority.

As they adapt to investigate algorithms, combat digital discrimination, and address global challenges, they must remain what they have always been—the citizen’s champion, the institution’s conscience, and democracy’s guardian.

In a world where institutional power continues to grow and concentrate, the humble yet powerful office of the Ombudsman stands as a beacon of hope that justice and transparency can prevail, one complaint, one investigation, one reform at a time.

An Ombudsmann investigates complaints from citizens, employees, or consumers about unfair treatment, maladministration, or unethical practices. They act as independent mediators, ensuring fairness, justice, and accountability in institutions.